Parker Solar Probe Images Venus on Flyby

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe images the surface of Venus during a recent flyby.

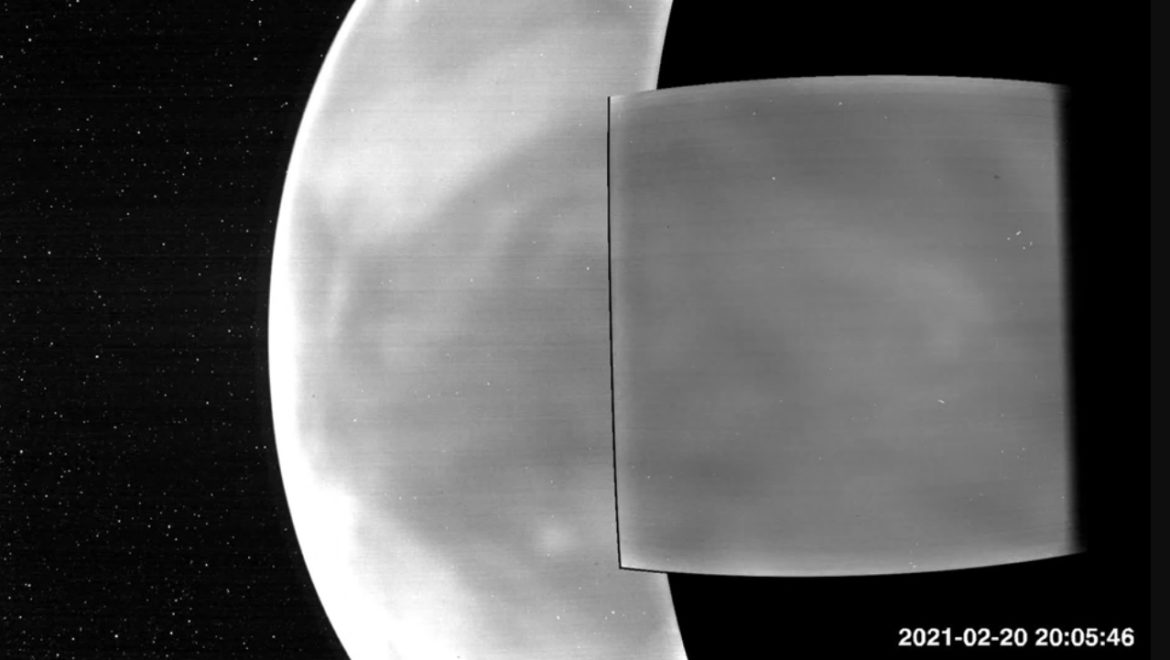

Venus, imaged by Parker’s WISPR instrument. NASA/GSFC

You’ve never seen Venus like this. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe accomplished a first during a recent flyby past the planet Venus, imaging the blistering nighttime surface of the planet from space.

The first image pass occurred during the mission’s third flyby in July 2020, followed by a fourth pass on February 20th 2021 at a distance of just under 2,400 kilometers from the Venusian cloudtops. The images are courtesy of Parker’s Wide-Field Imager (WISPR), which can image in the visible light into the near-infrared. The flybys were part of seven planned gravitational assists past Venus, on Parker’s trek into the inner solar system to study the Sun.

Launched on August 12th, 2018 from Cape Canaveral atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket, Parker Solar Probe is designed primarily to study the Sun close up. To this end, the mission will make several looping perihelion passes, getting as close as 6.9 million kilometers (just under 10 solar radii) from the Sun and moving at over 690,000 kilometers per hour by 2025. (Read more about Parker Solar Probe here.)

Though the mission is designed for solar astronomy, the Parker Solar Probe is also giving us some unique perspectives of enigmatic Venus during each pass. The images from WISPR show diverse surface features, including plains, rugged terrain and plateaus. A luminescent halo due to the tenuous presence of oxygen can even be seen in the video.

“We’re thrilled with the science insights Parker Solar Probe has provided thus far,” says Nicola Fox (NASA Headquarters-Heliophysics Division) in a recent press release. “Parker continues to outperform our expectations, and we are excited that these novel observations taken during our gravity assist maneuver can help advance Venus research in unexpected ways.”

Remember, though, we’re seeing a nighttime view of the surface though a thick blanket of clouds: that surface is glowing in the infrared because its extremely hot, in the range of 460 Celsius. The extreme heat and pressure on the surface of Venus (90 times that of sea level here on Earth) assured that Venera missions sent to the planet by the Soviet Union in the 1970s only lasted a scant few hours before succumbing to the harsh environment.

Why Imaging Venus is Hard

It’s a cosmic irony that the brightest and closest planet in the skies of Earth is also perpetually shrouded in clouds, and presents a blank white disk. We’ve only just begun to pull back the veil on mysterious Venus with the advent of the Space Age, to reveal a hellscape of a world. The persistent glow captured by Parker may even explain a curious phenomena on Venus reported by observers over the centuries, known as ‘ashen light.’ This is a faint glow perceived across the planet’s night side. On the Moon, Ashen light is easy to explain, as sunlight reflected off the Earth… Venus, however, has no convenient nearby reflector in space.

What’s Next for Parker

Though WISPR was designed to study the solar wind, its also proving its worth looking at Venus as well. The initial plans were to study the Venusian cloud flow patterns, but it actually saw all the way down to the surface of the planet, which surprised researchers.

The Electromagnetic Fields Investigation (FIELDS) instrument also used radio wave detections to characterize how the planet’s atmosphere interacts with the 11-year solar cycle, and WISPR also caught sight of the tenuous dust ring surrounding Venus in its orbit.

Next, Parker will make six more perihelion passes near the Sun in 2022 and early 2023, followed by the penultimate pass 3,939 kilometers from Venus on August 21st, 2023.

Parker is a great example of how versatile missions can produce unexpected science results.